My daughter has asked me to write about my mother, and I hesitate. I immediately seek out other themes, such as current events, current associations, or the spring light that hits the Iranian carpet in my living room. With its strong summer rays, it will fade the color of pomegranate in the evening light that soaks my carpet . Or, I think about my striving to sustain physical sovereignty by engaging in exercises that will make my thighs firm and supple, revealing why there’s a tennis ball amongst yellow oranges on my untidy table. The tennis ball is there; ready to be used in my free time, to keep my grip intact.

My mother wouldn’t have thought of these elements in her everyday life. She’d announced to her journal, a diary that nobody would come to influence or to the epistemology to open after her death. In her diary, she would have written about the weather, whom she had met that day, the umbrella that contorted in the western wind, and the wet coat she had because a car that passed her too closely, to the debris weather when she went over Puddefjord in Bergen where she lived.

The diary is for some reason on my nightstand. It’s there more for show and for the beauty of its Chinese jacket. It is not there because it’s content fills me with knowledge of her inner life. Sometimes I open it, but it doesn’t reveal the secrets of her because my mother couldn’t write down secrets. For her secrets were put into words during long breakfasts, while she drank black coffee and ate soft-boiled eggs. Through everyday pursuits, she created stories of her own and granny’s life, stories that could be written down in the diary. The fear of the truth was made harmless in her trivial words, but was dangerous to read in the elegant discretion in her writing. She could not write, just talk, so she created the writer in me. The internal pressure within her was transferred to me, and this pressure made me want to reveal the truth.

Stories from our public life are the building blocks for novels, manuscripts and films. Stories that still hold a place in my life and that I still yearn to create after forty years. I cannot let my mother or my grandma go. They live inside me, they are me, and they are not me. Boundaries are drawn, shifted, and whispered out. I run fast, but both my mother and grandmother are coming closer and closer as I get older. And now that I can’t run as fast anymore, they have reached me again.

One night in Los Angeles about a year ago, I sat awake on a couch in a small villa in Realto. I sat there in the dark and wrote the beginning of a novel. While I was mid-sentence, suddenly, my late mother was in the room. She sat there and stared at me in her cardigan and tight skirt, as she used to dress. She sat there in front of me and asked if I had seen her mother. She needed her mother, she said. An ascending soul from the sky, defying the universe to find her mother, but not to find me, as I had hoped.

No, my mother was tired of being a mother. She initially wanted to be a daughter. She would not be responsible for me anymore. I was not what she expected. She had created an actor, not a director. She had created an eternally young woman, a woman who was celebrated and molded by men, not one that was old and would shape her own image of the world. And most importantly, a daughter who defines her domain in her novels and movies. She would not allow it anymore. Now she would change my profile and be seen as the one she was. Mother also claimed that the public had no interest in mothers. For the future, she would play the lead role as daughter. My daughter. I would be her mother. She could no longer see the difference between me and her mother. I was her mother. Thus my mother came to earth to be my daughter.

I was free. Free from my mother, but not free from my own mother’s role. Without mother, no freedom, no-one to free myself from. Who am I then? It hit me.

A Mother’s look at me has been crucial: I had taken on the battles she couldn’t fight, creating the dramas she had written about in her diary. I would take her side, and I had shown her compassion and support by doing so. I was going to win the battles with my father that she could not. I would fight and love the same man all my life, as she could not, and follow him into his old age and death.

This is my project. A novel worthy, but not ready yet. To write her life, is to write our foremother’s life. We cannot distinguish where one of us ends and the other begins.

My advice: Keep your grip intact and your thighs strong. Life is a long walk, It’s sometimes dark, but there’s light too. We move in the same direction and we go in packs.

Written by my mother Vibeke Lokkeberg for Notebook.

Translated from Norwegian by Tonje Kristiansen

Editor Dana Dodge

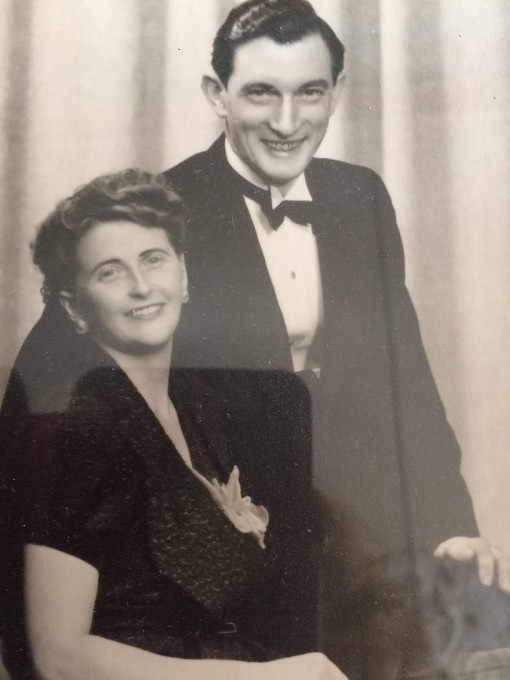

Photos are private of my grandmother Johanne Beate Kleivdal and her husband and family photo of my sister Marie Kristiansen, my mother and I.

All rights Tonje Kristiansen